Forty-five years after Osho gave a historic discourse on youth, I am narrating those words for the first time here

The wind cut through our face like icicles. It was an early January morning in 1970. The entire Patna railway station was still asleep inside the blanket of thick mist. A few tea vendors were ready to set up their stalls. Some were rubbing their frozen hands together in a desperate attempt to heat themselves. Winter had unleashed her force ruthlessly and yet a happy premonition kept me warm from inside.

Osho, who was known as Acharya Rajneesh in those days, was arriving by Toofan Express at six a.m. We had invited Acharyashree for Satsang and public discourses in Patna for four days. In the first two days, Acharyashree gave public discourses on various issues. On the third day, we had organised a talk programme at Patna College of Engineering, where I was a civil-engineering student. Acharyashree’s presence was a sheer tour-de-force. It was magical, almost unbelievable, how people were transformed in his presence. But at the same time, it was equally unbelievable how the general public, who had never met or heard him, harboured bitter, groundless suspicions towards him that almost bordered on antipathy.

That unrecorded speech

We had two political factions among the students in our university, the Communist-Socialist wing and Janasangh, the rightist wing. Incidentally, Osho had given a public discourse on communism, which was later compiled as Beware of Socialism, whereby infuriating the communists and not long ago, he had an argument with Shankaracharya of Puri in the World Religion Conference, which had upset the Janasanghis equally, if not more. So, as we started making preparations for his talk I was approached by both the factions with threats of assault if Acharyashree was to speak anything against either communism or religion. I pleaded Acharyashree over and again not to speak on either of the topics and instead give an address on youth issues. He had reassured me.Yet, I was nervous with anticipation.

It has been 45 years since Osho gave that historic discourse, which could not be recorded for the lack of a recorder. I am narrating those words for the first time here. But as I plunge into my memory and revisit that day again, it surprises me how his words still ring true and relevant to this day.

“My beloveds,” Acharyashree began the discourse. “I have been told repeatedly by our organisers to speak on the issues related to the youth. But whom do I speak to? I see no youths in this country. Here, a child is born and becomes old without ever entering into youth. If we had any youth in this country we would not have to wait for Edmund Hillary from New Zealand to climb the Himalaya. How long since we have romanced with the nature, how long since we tended to the calls of adventure? No, I see no youth here. No one dares to respond to the call of rebellion anymore. The fires in our hearts have been blown out. All that remains of it are a few dying embers, without any rebel who would dare to fan them to flames again.”

A strange stillness had descended. None dared to move. It felt sacrilegious to even breathe. The audience was transfixed. Just then Acharyashree looked at the audience and said, “Why are many of you staying so far away when there is so much space in the front?”

We had made seating arrangements in such a way that the girls were seated in the front rows, separated from the boys. This was a general practice. It was believed that the only way to preserve our sexual moral values was by creating as deep schism between boys and girls. When Acharyashree said that, the boys all ran towards the girls as though they had awoken from a spell and once seated, assumed the previous state of bewitchment again.

“Youth means rebellion,” Acharyashree went on. “It means courage, it means being a daredevil again. But we don’t have a tradition of rebellion in this country. This is not surprising that we had the tradition of child-marriage here. A child is

born and before he enters his sixteenth year, he becomes a father. A father can never be a youth; he will always be an old man full of responsibilities, regardless of his age. Now we have postponed the marriageable age but the psychology remains the same. This is why we don’t have rebels in this country.”

“It is no coincidence that the prisons and universities in this country are designed in the same style. They almost look similar from the outside and unfortunately, aren’t much different from each other either. The English were interested in producing clerks not rebels. They wanted to mass-produce clerks, who will enter into this slavery without ever questioning its validity. I call that man a genius, who comes out of the university without destroying his intelligence. The university is a mechanism to destroy genius, spontaneity and rebellion. The organiser had told me over and again to speak on youth issues but it seems, despite his age, he himself isn’t so youthful. Otherwise, what is the logic behind keeping boys and girls separately? I am against such a repressive vision. This forceful deprivation creates repressed, miserable creatures and gives birth to all kinds of sexual perversions.”

Acharyashree’s words cut through my conditioning just as enormous waterfalls cut through ancient mountains. “I want to provoke the youth in you,” Acharyashree was saying. “This is my crime. I want to rekindle that dying fire inside you again.”

Unchained spirits

Acharyashree finished his discourse right on time. The campus was reverberating with thunderous round of applause. The students stood up from their chairs and kept on clapping. A lump had risen in my throat. Tears rolled down my cheeks as I continued to clap. There were no communists, no Janasanghis. In their stead, I could only see the flames of light, burning brightly, overlapping each other. It was overwhelming. We were all burning, alighted, enflamed.

As Acharyashree walked down the aisle, students and professors alike rushed to hug him and get his autograph. There was such frenzy that people were picking littered papers to get his autograph. We had to wrestle with the crowd to escort him safely to the car.

When I came back to the campus, the students had left. There were piles of bricks and pebbles under many chairs. I knew the communists and Janasanghis were earnest when theythreatened of physical assault earlier. But when they left the campus that day, they had not just left those stones but the deadweight in their hearts too. I took a deep breath. The earth was not under the spell of gravity that day. We were all levitating. The sky was beckoning and the flames had leapt upwards, combusting all ropes of conditioning that suffocated the spirit of rebellion.

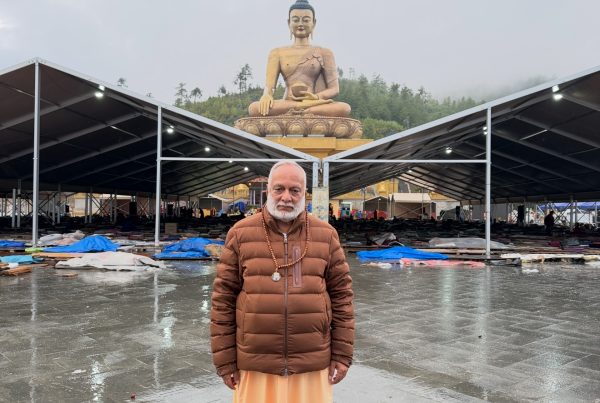

Anand Arun is founder and coordinator of Osho Tapoban—an international commune and forest treat centre